The ADA’s good intentions, and the real world

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (00:00):

Say you want to go shopping. Many of us don't have to think about cracked sidewalks, working automatic doors, or whether store owners even want us inside. But tallying up obstacles is part of a normal trip for someone using a wheelchair.

DAMITRA PENNY (00:14):

And she asked me, what did I want from this? And I said, "Well, I just want to be able to shop anywhere I want to shop."

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (00:22):

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 was supposed to make getting around easy and guarantee basic civil rights for people with any disability. And sometimes it works,

but not always. For the ADA's 30th anniversary, PublicSource and Unabridged Press explore how the act impacts life today. Our project is called ADA at 30: Accessibility in Pittsburgh. In this podcast, we're focusing on physical accessibility. We're talking with national disability advocates, Alisa Grishman and Josie Badger. They live in greater Pittsburgh and both use wheelchairs. Producer Tony Ganzer is here too. I'm Jennifer Szweda Jordan of Unabridged Press. Hi, everyone.

JOSIE BADGER (01:07):

Hi.

ALISA GRISHMAN (01:08):

Hello.

Damitra Penny, who often uses a wheelchair, was told she couldn't enter a section of a store because she'd knock things over. She says she just wanted to shop, not end up filing a lawsuit. (Courtesy photo)

Who owns the sidewalks?

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (01:09):

Alisa, you live in a wonderful, I think, very bus-able urban area in Pittsburgh. We'll get more to the sticking points in conversations with the ADA coordinators, but what's the best example of accessibility you've experienced—what's your favorite town?

ALISA GRISHMAN (01:26):

My favorite town in terms of accessibility is honestly where my parents live in New Jersey. The city owns all the sidewalks. People pay a little bit of extra property tax and they are immaculate. My wheelchair just glides over. I don't worry about bumps. I don't worry about anything. In the main shopping area, I can think of maybe three exceptions where there are stores that aren't accessible, but otherwise they're all at street level and you can get in and out. And it's just the most beautiful thing in this little suburban town in North Jersey.

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (02:12):

Josie. How about you?

Alaska’s aging population and tourism equals ease of travel

JOSIE BADGER (02:14):

There have been a lot of honestly great examples of towns that have been made accessible, even older towns. But as I was sitting here thinking about what is the best one, interestingly enough, I think when I've been in Alaska, some of that vacation was most accessible. And I think some of that has to do with it being built up later and also the amount of individuals that travel there who are older that need accessibility. So they've done a beautiful job at integrating a lot of curb cuts, and accessible transportation into all of their sites and towns.

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (03:01):

Yeah. When you said later, you mean like Pittsburgh's an old, I mean, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and us on the East Coast are older than Alaska. And that sort of thing.

JOSIE BADGER (03:12):

I mean, technically they're the same age, but when you're looking at how they were built up and a lot of the purpose was for tourism, then you can see why accessibility really mattered.

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (03:25):

Okay. We can go back to Alisa for the worst.

Harrisburg: 'Hot mess?'

ALISA GRISHMAN (03:30):

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The capital of our state is a hot mess. The sidewalks are terrible. The curb cuts are terrible. The Capitol Building is awful. I was there last year for a big press conference and they even told us which bathroom was the most accessible bathroom in the State Capitol Building and I couldn't get my wheelchair into the stall. I was so disappointed because I had an entire day before the press conference to wander around and I couldn't get into any of the stores locations. Like even, I went into a brewery and within, I could get into the main thing, but then all the side areas had steps to get in. It just was depressing how inaccessible our state capital is. It's awful.

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (04:40):

So Governor Tom Wolf, I hope you're listening as well as every legislator and citizen in this state. Josie, Alisa has taken Harrisburg. So if that was yours, you need to pick something else.

The trouble with Switzerland

JOSIE BADGER (04:51):

Oh, shucks. I think we can look at it a couple different ways. When we look at America, a lot of older cities are much more difficult and that's not an excuse. I think that it is believed that there's a grandfather clause and there's no such thing anymore to the ADA. But to be honest, looking globally when I went to Switzerland, the accessibility was horrendous and one of the reasons is that making any building or transportation accessible is by choice. It is not required. So curb cuts, some of them exist, some don't. So on transportation you can get on a train, but not get off. It's a tricky situation. But I think that ... well now when I went there I used a power scooter and scooters are not something that's used in Europe. So they just didn't know what to do with me.

TONY GANZER (05:58):

Oh, that's interesting. I was a correspondent in Switzerland for three and a half years, and there's such an awareness for social issues and accessibility issues, it's really interesting to hear your perspective. And also comparing it to Alaska that we were saying that, it's built for tourism. Well Switzerland's economy is mostly tourism, also pharmaceuticals and textiles a little bit, and chocolate. But tourism is a huge part of the GDP. So really interesting to compare that.

JOSIE BADGER (06:28):

As you said Tony, that so much of it is based on tourism and so a lot of the stores are accessible. And something so fascinating to me was that the old, old churches were accessible, but that's because they wanted us there. They wanted us to tour versus America where the Americans with Disabilities Act does not include religious facilities.

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (06:55):

And as a promo for another podcast in this ADA series, we do have a reporter who looked into Pittsburgh-area accessibility and houses of worship. Josie. I just want to, two questions. You said you couldn't get off the train, I assume you could get eventually off the train, but some platforms are not of the height that allows you to get off at the spot you want.

JOSIE BADGER (07:18):

That's right. I boarded in Zurich and I think we were trying to get off in Bern. Fortunately there were two men that saw us struggling and lifted me out, which is a problem in itself. But fortunately we're still not riding around the train in Switzerland, six years later.

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (07:38):

And the power scooter you mentioned, because I'm going to, once you say that, I imagine the little things on the road that you know are lesser than a motorcycle.

JOSIE BADGER (07:47):

No, I'm referring to like the gogo little older people's scooter.

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (07:55):

Supermarket?

JOSIE BADGER (07:56):

Yeah, yeah. I don't have the beeping back up or baskets on it, but yes.

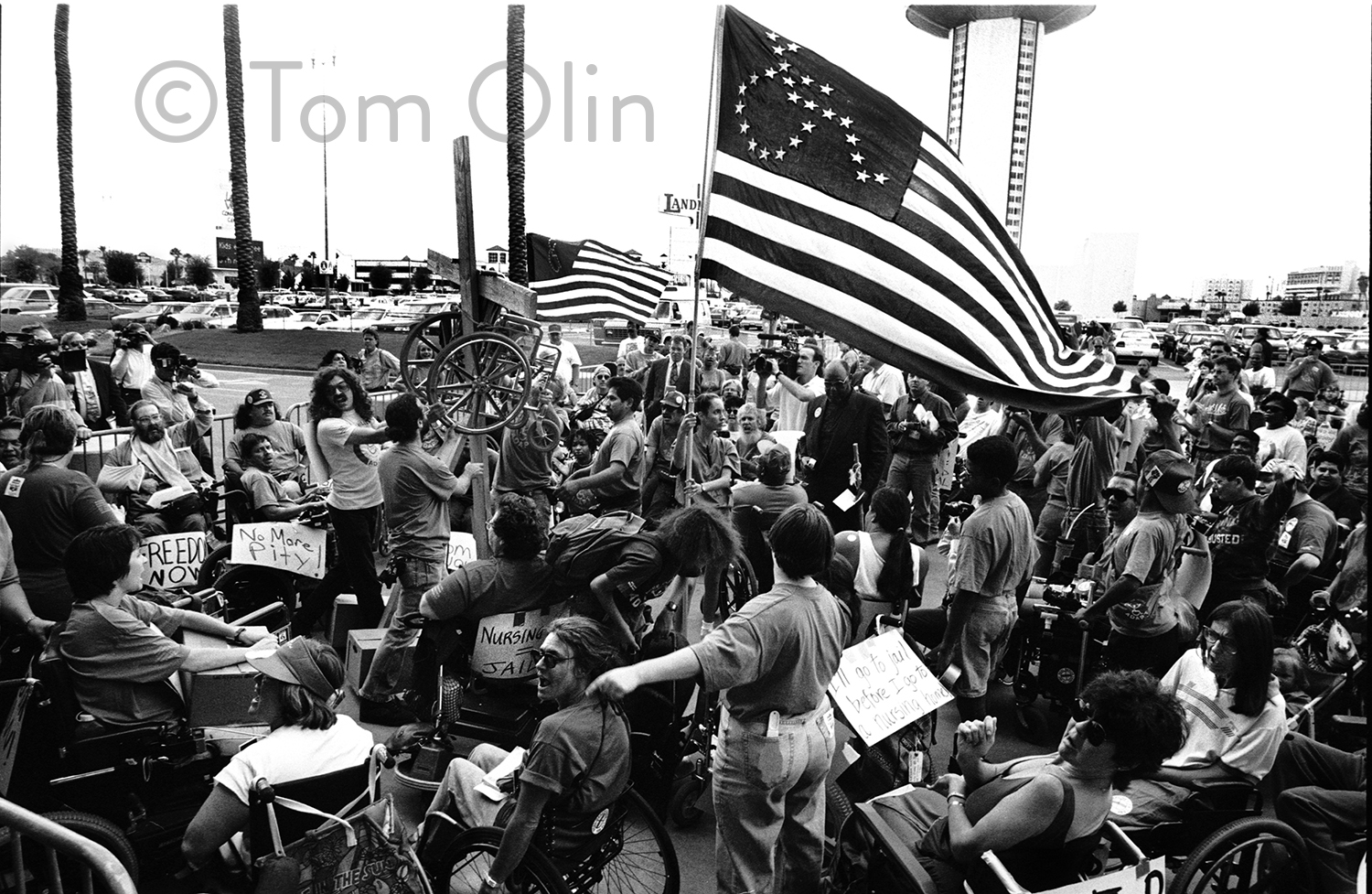

In Philadelphia, the same year the ADA was passed, protesters from the national grassroots disability rights group ADAPT demanded access to buses. Pittsburgh activist Alisa Grishman says getting around Philadelphia is still spotty due to the condition of sidewalks. (Used with permission. © Tom Olin – Tom Olin Collection.)

Survey says: Pittsburgh and Pennsylvania vs. the world

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (08:03):

So we did circulate an online poll. I feel like it's Family Feud time with some similar questions about Pittsburgh and other areas. It was unscientific, because we're not scientists and it was not carefully vetted for type of person. It was just sent out and about 25 people got back to us online. Tony, what's the short list of other people's best and worst places?

TONY GANZER (08:35):

So most accessible places: Seattle is mentioned. Washington, D.C. is on our list twice. We've got a couple of people saying they're not sure. I think it's just general confusion as to what most accessible even means, maybe confused them. We've also got Philadelphia, which Alisa, you might have some opinions on that making the most list.

ALISA GRISHMAN (09:00):

Philadelphia is, I often say, any time I go to Philadelphia, I stop complaining about Pittsburgh streets for up to a month. Anytime I go to Harrisburg, I stop complaining about Philadelphia streets for up to a month. Some parts, and in fact here, it goes back to the tourism. When you go to Philadelphia and you get to places like the Liberty Bell, things like that, sidewalks are great. There's curb cuts, there's entrance accessibility, but if you're going to the rest of the city, I've hit curb cuts that are too steep and broken up to actually get up and there's cobble stones everywhere that are uneven and hard to get across. And yeah, it's a mess.

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (09:55):

I also want to say when Josie mentioned Alaska and a lot of people in our part of the world, the Northeast, say the problems with streets are not just the age, but our climate. And you know, Alaska's got pretty cold weather up there as far as I know. But perhaps I'm not a city planner, perhaps it's the fluctuation that's more problematic, the heat and cold and expansion and contraction. But whatever it is, it seems like somebody ought to be able to figure it out.

Rural life can be rough

JOSIE BADGER (10:29):

And let me also mention these were some of the bigger towns in Alaska. We know that there's a huge percentage of people with disabilities who are in small native villages who have disabilities and don't have access. And so I also want to make sure we're not overlooking that.

TONY GANZER (10:48):

Well, taking a look at our poll, the least accessible places, rural communities made the list, which is a broad stroke, but talks to what you're mentioning there, Josie. Also on the list, most cities are not accessible. New York City is a bit more specific.

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (11:08):

Somebody just answered that way, right?

TONY GANZER (11:10):

Right. Yeah.

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (11:12):

Yeah.

TONY GANZER (11:12):

They said most. Yeah. Bradford, Pennsylvania. Rockingham, Virginia, very specific now. Western PA suburbs. Atlanta. Anywhere in Europe. I think a lot of experiences are matching what our panel thinks here.

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (11:34):

And, quickly, Josie you're in a rural area.

JOSIE BADGER (11:36):

I am. So I live about an hour north of the city and what kind of stinks is I can't even get out of my driveway because we don't have sidewalks and the road has been cut down so much that I get stuck. So yes, I echo, rural and even small towns.

Leaving for Las Vegas (and Dallas)

ALISA GRISHMAN (11:59):

Can I say, I am genuinely surprised that we haven't heard

Las Vegas on the very accessible towns. I would have put that except I haven't personally been, but my boyfriend has been, and it is 100% completely designed to be a tourist town, but especially catering to a lot of older adults. He talked about how everything, everything is designed to be accessible because there are so many people who go there who use assistive devices. And so it's interesting how tourism keeps coming up as being so important for driving accessibility.

JOSIE BADGER (12:46):

And Alisa, I've been to Vegas a couple of times—once for a disability conference and absolutely great public transportation. The taxis, they are set for accessibility. I think that one concern is the amount of smoking that still goes on so individuals with any respiratory problems, may struggle there.

ALISA GRISHMAN (13:11):

That's good to know.

TONY GANZER (13:13):

We spoke to John Duvall, a friend of the show who traveled to Dallas and he talked about taxis. You mentioned that Josie. And he said he had a real problem with taxis.

JON DUVALL (13:24):

I didn't reserve any accessible transportation or anything because I figured Dallas is a huge city. I'll be able to find an accessible taxi or something once I get down there from the airport to the hotel I was staying at. And when I got down there, I realized that Dallas pretty much has absolutely no accessible taxis. I contacted the big companies like Yellow Cab and all those types of places, and they all told me, "Well, did you try Uber or Lyft?" I think most people know that even in the bigger cities, so far Uber and Lyft and the ride sharing places don't have accessible transportation either because people don't have accessible transportation as their own vehicles.

JON DUVALL (14:01):

But anyway, it took me about six hours I think, to get to the hotel after calling every place that I could think of. Basically everyone said that all they had was paratransit there and you have to reserve that days before. So I ended up taking a bus over to their rail train station thing and then got to within about a mile from the hotel and then tried to take the sidewalks the rest of the way. It just so happened that the hotel I was staying at, it didn't have sidewalks that went to it. Comparing that to Pittsburgh, obviously I'm very happy that Pittsburgh does have accessible taxis, I think in all of their major taxi companies here in the city. So that, that's a positive related to Pittsburgh.

While Las Vegas is considered very accessible today, it's still been subject to protests over the years by ADAPT, a disability rights organization founded in 1978. Dozens of ADAPT members at this protest action hung a wheelchair on a cross and carried an American flag with a wheelchair outlined in stars. (Used with permission. © Tom Olin – Tom Olin Collection.)

Accessible taxicabs rare and costly

JOSIE BADGER (14:43):

I want to add to what Jonathan mentioned was, that in most towns and cities you cannot just land somewhere and get a taxi that's accessible. There was one time that I was flying to Montana and because of multiple flight debacles I got stuck in Colorado. And they're like, "Oh, don't worry, we'll get you a taxi." Well, it was midnight and they didn't understand that that's not something you can just do. Sure, there's taxis available all night for people who don't need access but a lot of the accessible cabs are actually owned by the drivers.

TONY GANZER (15:29):

I wonder if we can compare that to Pittsburgh, kind of bring it back. I went to

wheelchairtravel.org—they have ratings of different cities and one of the things they said about Pittsburgh taxis: long wait times. If you need it in the morning or the night time, you would need 12 to 24 hours notice. I wonder if that's your

ALISA GRISHMAN (15:50):

Definitely, yes. It's so, so rare that I bother trying to get a taxi. There has to be a really good reason. And for that, I tend to schedule a day in advance.

JOSIE BADGER (16:05):

And I know it's illegal, but they work around it, often accessible cabs are significantly more expensive than regular cabs.

Unfriendly doors and stores

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (16:19):

I think it's important that we hear a few more examples of how the challenge of accessibility is playing out in the real world. Tony, you had a conversation with another woman from our region.

TONY GANZER (16:29):

Yeah. One person I spoke with is Damitra Penny.

DAMITRA PENNY (16:32):

Penny, like the coin. I live in Baldwin, Pa.

TONY GANZER (16:36):

That's in Allegheny County, but she's from Pittsburgh.

DAMITRA PENNY (16:39):

I use a power chair. It was a product of domestic violence. I am a grandmother too, a mother of three successful children. Thank God.

TONY GANZER (16:52):

Penny told me one of the things that irks her the most are businesses that say they have an accessible door, but it's not actually accessible.

DAMITRA PENNY (17:01):

The door, there's no push button, there's nothing. There's just a sign that says that has the wheelchair on there and I'm like "Okay."

TONY GANZER (17:08):

Another problem can be places that might not want wheelchair users in their shop. Penny says she was in a hair store looking for wigs while managing her lupus. She had been there before, had talked with the woman who owned it, but on this occasion…

DAMITRA PENNY (17:24):

The woman's husband, they both owned the store, he was there one time and he wouldn't let me back in the store into the wig section. He said that I would knock everything over. And I said, "Legally, you can't stop me from going in there." And I called the Human Relations Commission while I was sitting in the store.

TONY GANZER (17:46):

Penny explained she just wanted to be able to shop. And there was a brokered deal for ADA training and better accessibility in this store.

DAMITRA PENNY (17:57):

I think he thought I wanted money from him and I really didn't. I just want to be treated like everybody else.

What city and county governments can and can’t do

TONY GANZER (18:03):

One challenge in the ADA is that each town or state might have different agencies or priorities to deal with compliance. Here's Pittsburgh's ADA coordinator, Hillary Roman.

HILLARY ROMAN (18:16):

If it's a small enough entity that's fewer than 50 people, nobody actually has to be doing it. Obviously we have 135 municipalities here in Pittsburgh. I'm lucky enough that I get to, you know, the city is mine.

TONY GANZER (18:30):

Roman says there are many important parts to the ADA, but infrastructure and trying to line up laws and building codes, that can be a challenge.

HILLARY ROMAN (18:39):

Well, of course, infrastructure is just such a huge problem and it's not for lack of people being aware of it or lack of trying. It's just there are so many issues where one thing isn't congruent with another. So the building code isn't necessarily congruent with the federal law. It's just the way our legal system works. The whole 50 state thing, the whole decentralization thing, it makes it really hard. So you can have an overarching law like the ADA that is really broadly protective and you can come into these kind of absurd problems where people have accessible bathrooms without accessible entrances because we use a building code that's laid out, it's an international building code and how do we get it to become congruent with the ADA? Right? These laws are made at different times with different values and different players involved.

TONY GANZER (19:30):

And something to keep in mind about the ADA in general is that a lot of responsibility lies with someone who has a valid complaint, not necessarily an enforcement agency. Our advocate Josie Badger explained this to me.

JOSIE BADGER (19:44):

ADA coordinators are really important and unfortunately most of what they are able to do is that they can provide feedback. They can highlight issues.

They can bring people together, but there's not necessarily a structured enforcement to it. That's partially because of how the ADA was written. It was written to be enforced by individuals with disabilities through the judicial system. And so that means people with disabilities generally have to self advocate and when necessary use the legal system to bring about changes, which sometimes causes some division between businesses and people with disabilities and creating a fear of people with disabilities concerning lawsuits. Instead of doing it because they have to, because it's the law, they do it because they're afraid of being sued.

The Allegheny County and City of Pittsburgh Disability Task Force met by Zoom for the first time in June and plans to continue online meetings as an accessibility measure.

Getting to the ballot box: it’s getting better

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (20:51):

2020 is an election year, of course, and

voting access is required under the ADA. We talked about that with Caylin Snyder, ADA Coordinator for Allegheny County.

JOSIE BADGER (21:05):

Caylin, I'm super excited to hear that Pittsburgh and Allegheny County are moving forward with accessible voting machines. I'm north of the city and live in Lawrence County. And I was the first one to use an accessible voting machine up here in the boonies. And so it was a really cool experience because I actually was able to learn how to do it and teach some of the staff at the voting place how to use it. Do you feel that people who are staffing the places are fully aware of how to use them? Are they excited about it?

CAYLIN SNYDER (21:47):

Oh, I've heard a lot of feedback with how easy and cool the machines are. I think the training process has cut down a lot. I think it's just because it's new and foreign to them that some people are a little worried because there's so many different features of it. But after talking to people, once they go through the training, it seems pretty straightforward and easy for them. I think the more and more people are able to use the machines, I mean, who knows with coronavirus going on, but hopefully by the next election, more and more people can use it. It's just as easy as following the screen. So I think I'm really excited for us to move forward with it and I hope that the community provides a little more feedback on it because I want to make sure that the poll workers are comfortable with it, too.

JOSIE BADGER (22:36):

What I really liked personally about the voting machine is that you can have a clicker to pick your answers that you could use on the table or on your lap if you had some mobility problems. I just used also the audio describe part of it because I wanted to see if it worked well and it was so smooth. I think that something really important that I hope the county is doing is letting people know, letting voters know that these machines are out there and that they are available so that they're not worried about trying to get someone to help them vote now.

CAYLIN SNYDER (23:17):

Yeah. And we were even stressing during the primary election that anyone can use the machine. You don't have to have a disability. We were trying to encourage others to use it so they can spread awareness about it. We got all types of people trying it out and they were all really impressed with it. I hope that we get more feedback on it and see what other things about it. I think the coolest part is definitely the ADHD [inaudible 00:23:42] . You can do so much with it. It's really, really cool.

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (23:45):

What's the latest (this is Jennifer) with voting by mail? I know a lot of places, people have tried to make it that voting in person has to happen and for people, as Alisa has brought up a lot with her immunocompromised that for a long time they're probably not going to want to go out and feel safe in the community.

CAYLIN SNYDER (24:08):

Right. Yeah. They've been trying to encourage voter by mail and I know there were some hiccups with that. People, they brought it up before at the (city-county disability) task force meetings or other people from the public saying that, "I didn't get it in the mail," or "I got multiple copies." I think just because it was our first run with this and had a huge amount of voters. By now, I'm hoping by next election they'll have a smoother process and we'll get the elections division to be able to have better training for that and reach out to the public on how to make those correct steps.

CAYLIN SNYDER (24:45):

So yeah, I think the first one, it was definitely a learning process and hoping we can fix those hiccups for the next election.

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (24:53):

Alisa, how has your experience been in voting?

ALISA GRISHMAN (24:56):

It's a crapshoot, honestly. There are a couple of really accessible polling locations in the city and there's a couple that just really, really aren't. And in fact, I had a wonderful experience with my current polling location, which is in a firehouse. The first couple of times I went was really not accessible. The way they had a set of metal ramps set up, there wasn't a safe way to travel up the ramps and in the door. In fact, the employees at the fire station had to move machines around to get me in a back entrance, which was so lovely of them. The next time I went to vote, they had paved the steps into a long ramp to enter the firehouse. So, there's some wonderfully responsive places like that, but there are still a lot of polling locations in the city that are not accessible.

JOSIE BADGER (26:02):

I'll just jump in here. This is Josie. I think that this shows how important it is for people with disabilities to get out and vote. Because for me, I was the first person that used this machine and so I took the effort to learn it and help them learn how to use it. But just as Alisa said, she had to go utilize a non-accessible facility to teach them why it's important. And so I think that just emphasizes the importance of all of us getting out there to vote.

ALISA GRISHMAN (26:35):

Agreed.

CAYLIN SNYDER (26:36):

Yeah. I agree with both of you guys and I think that's a really important thing to go over. It's almost like an afterthought, which it can be so frustrating. You don't want the disability community to go out there and then they have to make that complaint or concern. We should already be inclusive and as accessible as possible. I think that's our job to try to break that afterthought, like, "Oh, let's accommodate later," rather than just jump the gun and plan to be inclusive. I agree with you guys. It's a good thing and a bad thing. We want the disability community to go out there, but I don't want them to feel like they have to correct every little thing. We should already be addressing it.

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (27:20):

And so are you the person to call if that's an issue in Allegheny County or what do people do when things like this come up?

CAYLIN SNYDER (27:28):

Typically you would contact the Elections Division. They have individuals who go out to polling locations and evaluate it. They have a checklist to make sure that they meet the minimum ADA requirements. If they don't meet the ADA requirements, they put up those portable ramps or down the line, like what happened with Alisa, they paved the whole way. So the elections team is usually the ones that addresses those concerns at polling locations. But sometimes again, because I'm the ADA Coordinator, I'm kind of like the middleman. If the public has a question or concern regarding the county departments and their accessibility, I relay it to them, report it and then follow up with that person.

JOSIE BADGER (28:10):

So we'll just share your cell phone number after this. Kidding.

Healthcare ethicist Josie Badger recording the podcast via Zoom. (Courtesy Photo)

CAYLIN SNYDER (28:16):

I would love to chat with everyone. The more people the better. I'm just one person.

The small roads to change

JENNIFER SZWEDA JORDAN (28:33):

So why is accessibility hard to achieve? Well, business owners, for example, just might not want to change—many say they don't have the resources for, say, a ramp. When that happens, a person with a disability—or maybe a nonprofit that represents individual—has to argue for accommodations. Many times, that comes to filing lawsuits. Our next episode features Jay Hornack, a University of Pittsburgh law school professor. When the ADA was passed, it changed the course of his legal career. I hope you'll listen to that and explore all of our work at adapittsburgh.com. Thanks to Josie Badger and Alisa Grishman. This program's producer is Tony Ganzer. I'm Jennifer Szweda Jordan with Unabridged Press. This project, ADA at 30: Accessibility in Pittsburgh is produced with PublicSource, with support from the FISA Foundation and assistance from the Center for Media Innovation at Point Park University. Thanks for listening.